Imagine it: the smoke-laden air of a dim club where the sound of fiddles and guitars bends through time and memory like ghosts in a dusty attic, only to be followed by something electric, something sharp enough to leave a permanent mark. Enter Carolyn Kendrick, a Los Angeles-based singer-songwriter whose voice wraps around you like velvet but with a dangerous edge, like a quiet whisper that ends in a knife’s gleam. Her latest release, Each Machine, feels less like an album and more like a journey, one that takes you deep into the cracked-open underbelly of American history and back out, slightly more broken but undeniably wiser.

URL: https://www.carolynkendrick.com/

Kendrick, known for years as a roving side musician, has now planted her flag firmly as a solo artist. This album is both an arrival and a revelation. Not that Kendrick is new to any stage—oh no, she’s crisscrossed this country, fiddling her way through festivals and back alleys alike, from Newport Folk Festival to the Savannah Music Festival, collecting accolades and admirers like hitchhikers. And she’s good at it—her Berklee College of Music polish runs like gold thread through the grit of her sound, both precise and wild in equal measure. Her past projects, like the duo The Page Turners, gave us a taste, but Each Machine is where she really blooms.

But don’t expect flowers. This album is darker, deeper—more coal mine than garden. Drawing from her research into the Satanic Panic for the hit podcast You’re Wrong About (you know the one—Podcast of the Year, iHeart Radio), Kendrick’s Each Machine digs into the dirty mythologies that shape America’s underbelly. These are folk songs for a modern world teetering on the edge. You hear it in tracks like “The Devil’s Nine Questions,” where her electric guitar crackles like fire underfoot, mixing with ancient hymns and pagan chants, a reimagining of the old murder ballads but with a modern-day shiver.

Each note of Each Machine reverberates with a kind of tension. It’s bluegrass reimagined, but also protest music that takes no prisoners. These songs are not meant to soothe; they are meant to provoke. And then there’s Kendrick herself—ethereal, yes, haunting, definitely, but there’s a devilish wit in her lyricism that keeps you off balance. Just when you think you know where she’s going, she veers left, pulls you into a dark alley of sound and leaves you standing there, wondering what just happened. “Hauntingly lovely,” Paste Magazine called her, but that doesn’t do it justice. It’s more like she takes beauty and cracks it open, lets it bleed out a bit, and then hands it back to you.

The album isn’t just music either. Kendrick’s entire release has an air of mysticism. The limited-edition 12″ vinyl, the accompanying zine filled with behind-the-scenes photography and personal essays—it’s all part of a broader ritual. You’re not just listening to an album; you’re stepping into her world, into the haunted space between history and myth, past and present. She presses on vinyl not just songs, but stories, folklore, and political unrest. The zine isn’t just an add-on, it’s part of the experience, like a grimoire guiding you through the sonic landscape Kendrick has built, her essays giving us a glimpse into the creation process.

And then there’s her influences, sprawling and eclectic: Aoife O’Donovan, Kaia Kater, Margo Price, Bruce Molsky—names that read like a map of modern folk royalty. But Carolyn isn’t just rubbing shoulders with greatness; she’s carving out her own place. When she shared the stage with these legends, she wasn’t just a backing musician. She was absorbing, learning, and now? Now, she’s showing us what she’s made of.

Yet, this album isn’t about resting on laurels. It’s not comfortable. Tracks like “Deadman’s Creek,” where Kendrick channels that age-old tradition of murder ballads, are unsettling, in the best way possible. This is Carolyn Kendrick pushing the boundaries of what folk music can be—political, dangerous, a little bit weird. There are electric guitar licks that slice through fiddle melodies like lightning striking a barn. It’s a sound that could fill a darkened cathedral just as easily as a backwoods juke joint.

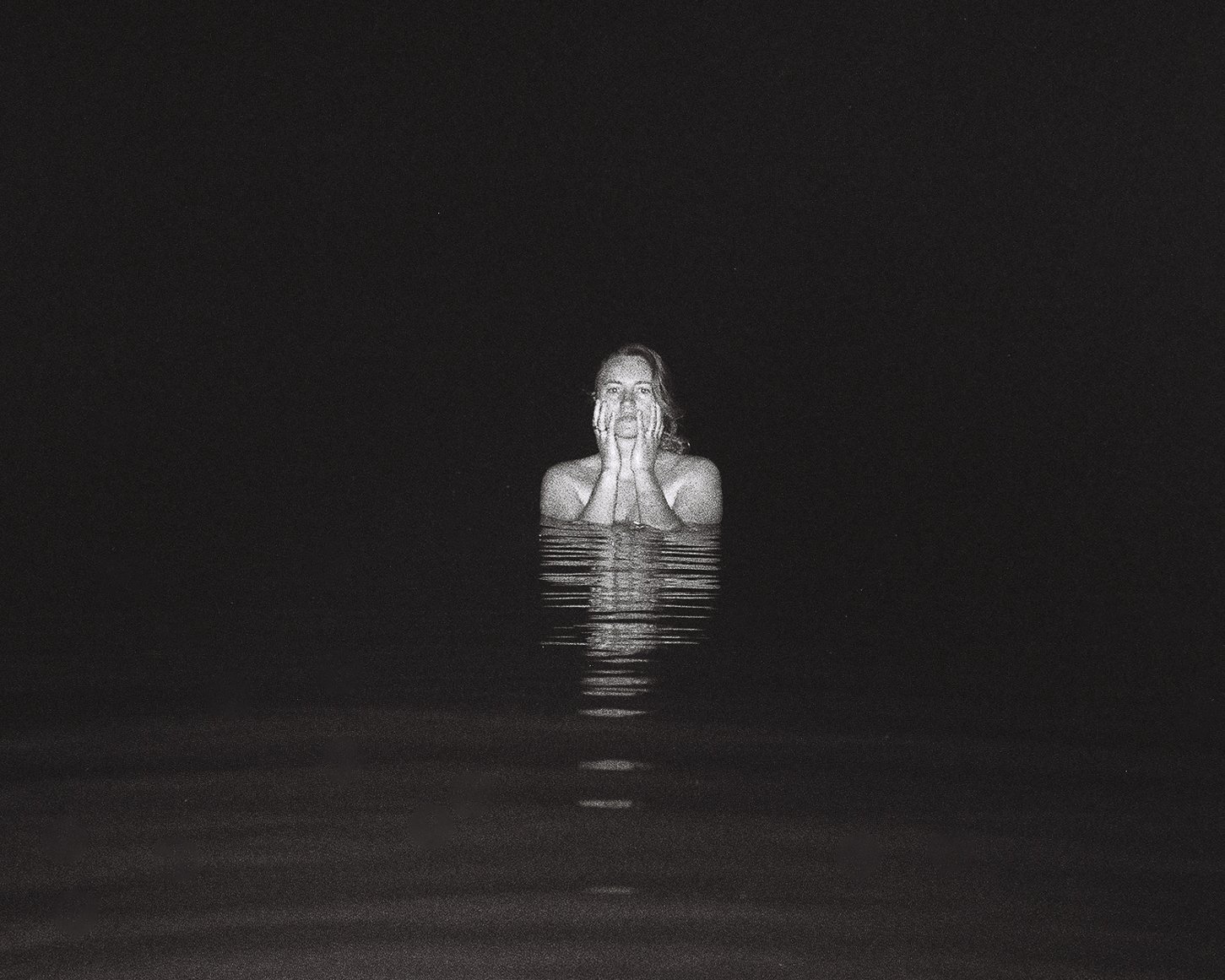

When you think of Carolyn Kendrick, maybe you picture a woman with a guitar, standing under a single spotlight. But with Each Machine, you need to picture something else—a conjurer, calling up old ghosts and setting them loose into the night, all while smiling softly from the shadows. This is not the same artist who gave us Tear Things Apart back in 2020, though you can trace the lines of growth. No, this is something fiercer, stranger, electric.

What you get in Each Machine is a time capsule cracked open. It is pagan hymns soaked in gasoline. It is a prayer and a curse all in one breath. Kendrick’s time on the road, her years as the fiddler standing just to the right of the spotlight, have sharpened her. Now, in the center, she’s both beautiful and dangerous, daring us to follow her deeper into the dark.

Garth Thomas