Just across the Great South Bay, a lagoon abutting Long Island’s South Shore, is Fire Island, including the iconic LGBTQ havens of Cherry Grove and The Pines. These oceanfront communities are among the few places gay men can go to be their true, authentic selves, without a second thought. Free from care or worry, and far from the condescending eyes of an increasingly homophobic society, Fire Island’s welcoming sands offer a true getaway for the children of the rainbow. For at least the past half-century, this isolated but alluring seaside cove has offered pleasures both libidinous and sublime, for the throngs of young (and not-so-young) men who ensconce themselves on its shores every summer. Aboard packed ferryboats they sail, full of the party spirit from the moment the vessel slips away from the dock; drag queens already in full regalia, and toned beach gods basking shirtless in the sun and sea breezes.

The arrival of these summer weekenders and performers brings the quiet piers to vibrant life, as the boys’ exuberance energizes everything. Of course, you know the Ferry must make land at The Pines just in time for Low Tea at the venerable Blue Whale. That’s the way things kick off, just after you’ve stepped off the boat, found the house you’ll stay at, and unpacked all your fabulous swag, Speedos, and de rigeur conch sandals. Then you flit over the boards to the Whale, hard by the Canteen, with the legendary Pavilion dance hall just astern. You rub shoulders with men famous and ordinary, and it’s a freewheeling celebration of gay life, in all its fierce flamboyance. In the back of your mind, you’re already thinking of a furtive stroll through the hidden, notorious Meat Rack, with perhaps a glimpse of the mysterious, clothing-optional Belvedere Hotel near Cherry Grove. Of course, that lovely vignette is Fire Island in summer—during a normal year.

Alas, 2020 has given us almost nothing that could be deemed “normal”, suffering as we are through the horrifying COVID-19 pandemic, which brought all our lives to a brutal, hard stop. Now with fearful eyes, behind protective face masks, we struggle to maintain our health and sanity while deep in the throes of lockdowns, travel restrictions, and an ongoing, global economic collapse. Indeed, the impact of this natural disaster was keenly felt by the LGBTQ+ community early on, as hundreds of Pride celebrations around the world were canceled. This was a sad harbinger of a bleak summer to come. However, weary of prolonged quarantines and the closure of most gay bars and clubs, the children grew restless by the Fourth Of July. Seeking perhaps a glimmer of normalcy in an uncertain time, they sojourned to The Pines despite the absence of scheduled events.

As these dispirited travelers alighted on the sunny pier (among them one “COVID Corey”, who ventured out to the Island knowing he was already ill with the virus), they roamed the dunes, looking for a good time. After the Suffolk County Police Marine Bureau broke up a beach gathering they estimated was “in the hundreds”, and another impromptu soiree in the Meat Rack, it somehow got out that a house party was taking place at local private time-share keeper Stephen Daniello’s lavish Pines villa just a few steps from the Pier. While Daniello, who also operates a separate private catering business, slept in his basement amid noisy HVAC machinery, a group of about 40 people materialized in his pool deck above. Once alerted by his houseboy to the unauthorized get-together, Daniello rushed topside and dispersed the gathering crowd. Although the deck was swiftly cleared, followed by a through deep-cleaning of the house, the damage was done. Along with the beach melees, a growing uproar over the presence of so many revelers during a time of plague, raised serious questions about what was happening on the remote island idyll.

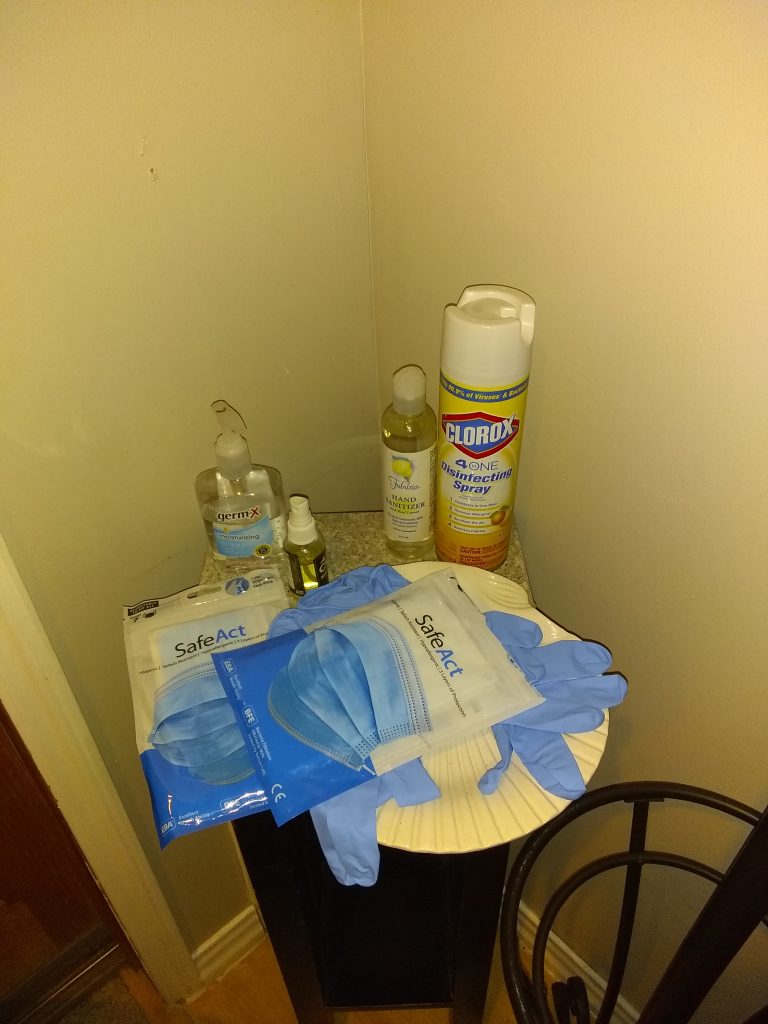

Fast-forward eight weeks: a warm, sunny Tuesday at the end of August. Now the usually bustling harbor at The Pines is tranquil, almost placid. Gone are the scores of beachgoers that filled the quay the month before. Here and there people lounge about, or ramble leisurely on their twos and threes, but certainly not in their tens and twenties as in an ordinary era. “I’ve been on the Island 19 years,” Daniello reflects, “and I’m not ready to call it quits yet. I want to see things come back.” As he has since his arrival at the villa in late spring, Daniello is being very circumspect about taking precautions for himself and his valued guests. “I myself have been COVID-tested several times, and I make sure my guests are well when they arrive and are well when they go home.” A close inspection of Daniello’s spacious accommodations bears this out: carefully placed masks, gloves, and hand sanitizers await guests at the patio entrance, touch surfaces are regularly scrubbed, and social distancing is the order of the day. “I need to make sure my visitors are comfortable,” Daniello notes, “that they can come here, have fun, but still be safe.” Even the pool gets examined and cleaned on alternate mornings.

Daniello’s diligence is likewise reflected in the activities of the local businesses, and the Fire Island Pines Property Owners Association (FIPPOA). “We want to make it through, so that when this pandemic is over, the guests come back with confidence,” a FIPPOA official, speaking anonymously, observed. “We want to let people know we’re doing our part now, too.” The little Fire Island Pines Fire Department, whose firehouse lies on the spine of the Island, stays vigilantly abreast of COVID developments, and is well-equipped to treat related medical emergencies. If you look at the cafes and the Pantry along the Pier, signage mandating mask usage and social distancing is everywhere apparent. All these steps are done with an eye towards balancing what reduced revenue is made, with preserving a safe environment for the tourists and locals alike.

Back at the villa, Daniello faces a tough decision. “I have to let the owners know by the end of October, if I’ll be here for the 2021 season,” the celebrity chef muses, “and I have to do this not knowing whether the virus will be gone by then.” His short-term plan is to stay on Fire Island until New Year’s Day, there to help support his neighbors with sustenance and solidarity. “If I can’t reopen next year, I’ll certainly be back in 2022, even if I’m in a different house,” Daniello confides. “I want another ten or fifteen yeas here before I retire.” For a community that has weathered Hurricane Sandy, other economic downturns, and the ever-shifting patterns of gay tourism, residents here are cautiously optimistic about the future. One townhouse owner remarked, “It takes a lot more than this to stop us from looking ahead.”

The sun slowly sets on the dunes and the undulating ocean. Even the seabirds above seem to be eager for a new tomorrow—a more tentative dawn, at least in the near-term, but the undeniable energy of even the die-hards who came out before summer was all gone, bespeaks a joyful return to happier days, just there over the horizon. Another summer will soon see the ferryboats full again, sashaying drag queens and all.