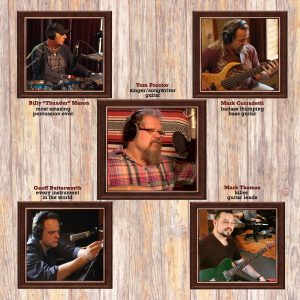

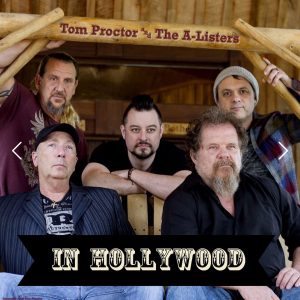

Tom Proctor, with his roles in 12 Years A Slave and True Detective, has been around the block in showbiz. Now, he’s embarking on a country career, with the help of his talented band The A-Listers. I talked with him a bit about his musical odyssey.

EB: You have an impressive acting career to go with your musical efforts. Are there ever any difficulties in balancing acting with music?

Oh my gosh, yes. Even though one enhances the other, you’ll find there’s a lot of actors who, once they get their acting career—you know, get to the point of being A-listers—then they venture into their music careers. They don’t usually try to do it simultaneously, and while I’ve had a good acting career and I work a lot, I’ve seen a lot—I’m not really what you’d call a top A-list actor. For example, Billy Bob Thornton took time off and started a band; Kiefer Sutherland formed a band, and it worked out really well because they were able to start off with a big-enough fanbase—people who would go see them even at cost prices. They fill a concert just based on their acting resumes. What I gather from a lot of the musicians in Nashville is that they fucking hate this! They resent it, because a lot of those guys can’t sing and don’t really have what it takes…whereas I’m still building my acting career. I’m a known actor, but not a name actor, if that makes sense. All the time in restaurants, I’ll get “I know you!” from someone. They think they know me from the gym, or from something like that. They don’t walk up and go “oh my gosh, you’re Billy Bob Thornton!” or “You’re Josh Brolin!” They don’t walk up and recognize right off the bat. And so, with that, I find that I have the same battle with building the band as someone just starting off with no name behind them. Another thing I ran into was, I booked my band, and they were called the A-Listers—and they really are the A-Listers. They’re the best of Nashville, like Tim McGraw’s old band member and these guys who are the top sessions musicians in Nashville. So, to get them on the album, I had to book Dark Horse Studios in December to be able to record in April. What happened was, in April, I got offered five episodes of True Detective, which I needed to increase my notability as an actor—and that’s where my main income comes from. I had to turn that down that part for the studio session. So the biggest block is, now you’re divided. You’re trying to promote two things at once, and just promoting your acting gig, at my level, is a fulltime job. I’m in a unique position where I can work on 20 films in a year, and make my entire living and be fine. But in between those films, I have to be working at finding the next film, and social media, and all the PR I can do to keep in the public eye. When I put this album out, I thought “okay, this gonna be easy.” I’ve got the best guys in Nashville, I booked the band, got an agent, and I’ll do the band as a part-time gig like a lot of actors do. Every actor’s got something they do on the side, and I wanted something that would actually help promote it [acting profile]. But, the thing that I found that surprised me is, even friends that have purchased the download call me back later and say “what the hell? Why didn’t you tell me it was great? I didn’t know you could sing, I didn’t know you could play!” And I say “Well, why did you buy the album, then?” And they say “I was just trying to be supportive, man!” It’s been fun, but it’s difficult, promoting an album.

EB: Have you had acting roles before where you got to use your musical talents?

Actually…no. And not only have I not gotten to use my musical talents, but I play a lotta bad guys, and do a lotta fight scenes. I’ve got black belts in five different systems, and I was a professional fighter who had 254 contact fights. But when it comes to long-hand form and fighting choreography—I have done fighting on some beautiful fights, and I never get to be the beautiful fighter. With my look, they never wanted me to look like I knew any martial arts at all. I had to throw an ugly punch, be a ballroom brawler, just an ugly thug. So, you know, he’s the guy that don’t know anything. So I end up training people to fight against the big thug. And I’ve done fight scenes with the top A-listers. I kidnapped Stallone on Escape Plan and tasered him, and fought Bruce Willis in Looper, and Jeffrey Dean Morgan and Jessica Chastain. So, I’m really good at fight scenes, but I always play the dumb barroom brawler. …now, every other one of my skills has come into play: my motorcycle riding, my horse riding, being an expert with bullwhips and even knives, all that’s come into play. But never my music. I was scheduled to play a small bit in a small indie film called Nation’s Fire, and they got behind on scheduling. Was a scene where he [the character] tell these people to come to the concert early because he’s gonna open the show. They got behind on schedule, and that got cut out, so…almost!

EB: On your newest record, you have songs themed around Hollywood and New Orleans. Do you find it easy to write about cities?

If you listen to the songs, they’re not about a city. They’re about a situation. All my songs are stories from the heart. Example: “Lost in New Orleans.” Some would say, “oh, it’s a song about a stripper.” But it’s not. It’s actually a song about a woman who—a true story—a woman who was the best mother I have ever seen. She was a great mom to this little boy, and she did what she had to do to take care of that little boy. Which happened to be working nights as a stripper. Then, later as I got to knew her, she managed to get her way out of that, into working at a restaurant and later managing a restaurant. But she did what she had to do at the time, which I thought was very admirable, and that’s what the song is about. The song “In Hollywood” is, again, a true story. About a real producer that really took advantage of young girls. The song was being written for a movie that was about this particular producer. All my songs, and I hate to say the stereotypical thing, but all my songs are made up of a few chords and the truth. And that’s why there’s so many people who can relate to them. There’s a deeper meaning to each song. If you listen to “Lost in New Orleans,” you’ll hear that this is not just a stripper, this is a mom who really cares about her kids.

EB: If Tom Proctor and the A-Listers had a mission statement, what would it be?

Hmm. It would be…to live. Simply, live. Without judgement, without barriers, follow your heart. That’s what everything in there is about. And the album’s dedicated to the working man—that’s what the song “Working Man” is all about. People who live, and work, and have integrity. Have fun! I don’t know, the mission statement would probably be… (pause). We’re in a time where our country is completely divided. But you listen to the songs about real people, you figure out we’re not all that different. We put our pants on one leg at a time…we all really want the same things. To be able to take care of our families…America is a family that is made by families. It’s weird, when you say mission statement, my mind automatically converts to somebody with an agenda. I don’t really have an agenda, I’m not trying to change the world or any of that. I just want my songs felt. I want my words heard. You know, my grandkids and I went to this outdoor show, The Greatest Show on Earth. And in the car on the way there, I found out my grandkids had never really heard my album. So I played it to see what they thought about it. And they really liked the album. Before the show, there was this other music playing, and they were dancing to it, really getting into it. And I said “can you understand the words, can you understand what they’re saying?” Because I was trying to figure out what the song was about. And he goes “no.” I ask my granddaughter the same thing, and she goes “no.” “But you like it?” “Yes.” The music made them feel something, and the words didn’t matter. In my songs, the words matter. You may not really catch the song without the words. Because I don’t think I’m really a top-notch musician—hell, I won the guitar in an arm-wrestling match, six or seven years ago. And I don’t even know what chords I’m playing, to be honest. I had a good team around me. They made charts and stuff that means nothing to me, and I know a lot of the chords now, thanks to them. But…I just want people to feel. There’s a song that says “when did you put it in a song,” and it’s all about a couple that was gonna break up. I put their life story in a song, so that they could see that they didn’t need to break up. That was a true story, and I was the guy with the guitar. And I hardly knew the couple. I just knew that they were getting divorced, and shouldn’t be. What happened was—and this is weird. I had had some accidents, was busted up, little money, and I was playing on the streets in New Orleans. I was a street musician. And I would do Bob Seger’s “Turn the Page,” and “Simple Man,” and stuff like that. There were some kinda wealthy business guys that had come down there, and they’d say “oh look! He sounds just like Charlie Daniels on ‘Simple Man!” They had good comments about my music. By then I had packed up, and I had done what we street musicians called the day shift. If you have a spot, you turn it over to someone else at night so that they can make a living. And I was walking back, and some of these guys said “hey, there’s that guy! Come in here and play “Simple Man.” And you just don’t go into a bar and play when you’re a street musician—it’s kind of an unwritten law, cuz then you’re screwing with the other musicians, and their positions. But I looked up at the guy at the bar, and he nodded for me to come in and do one song, because these guys were spending a lot of money. And they offered me $150 to go in there and play one song. And as I started to walk to the stage, I saw this couple sitting at a table, and they were the only ones in the place not having a good time. And I saw a bunch of papers on their table. So my curiosity was to kind of snoop a look, because thick papers in a restaurant often mean someone’s doing a film project or a script. And I had gotten busted up, but I was getting back on my feet and getting ready to do more movies, and I was looking for every opportunity. As I went by the table, I realized that these were not scripts. And then I can tell by the look on their faces that these were divorce papers. As I was setting up, the song started formulating in my head. That was when I played “When Did You Put It In a Song.” The couple was in tears. Afterwards, when I talked to them, the guy said “how did you know, and when did you make it into a song? When did you know?” And the truth was, I didn’t. I made up the song right there. It’s a true story about that married couple. In the song the man says “I’m at this café bar where we got our start, and we’re saying our final goodbyes. And the lawyers had the paper drawn up, and mine was already signed, to leave it all behind. He walked to the stage, picked up a guitar, took a shot, then he started a tune. And he looked in my eyes like he knew who I was, and said ‘son, this one’s for you.’’ These are the words I came up with on the spot. And in the second it goes “he knew about the day my little one was born, and the way that I felt when they sent him off to war, and the way that I lost my mind when he didn’t make it home. And he knew I took my pain to another woman’s bed, and he knew word for word all the things I had said. But somehow, from his song, she understood, and it was all good.” And that’s where the chorus comes in and says “how did you know about my ex-wife, how did you know about me and my whole damn life, how did you know all the things I done wrong, and when did you put it in a song?” The answer to that was, right then. That moment. And it happened that his boy did go to war, and he did lose a son, and that’s when their marriage did fall apart. And I’ve talked to him three times since when I’ve gone down there, and they’re still together. It was pretty crazy, but…I didn’t play the song the guys had paid me to come in and play. I played that one. I couldn’t get “Simple Man” in my head, but I couldn’t get that out of my head. I’ve got two more albums’ worth of songs that come from my heart, and all I care about is that they hit somebody else’s heart. With the song “Delete You,” I’ve had people say to me that it’s really the song about the people they tried to delete from their telephone. You know, that’s a good feeling.

EB: Do you have any unique or standout stories of touring or performing in your career?

In my music career? Well, my music career’s just started. Let me just tell you this—here’s the most fantastic story. My music career started when I was a little boy singing for my grandmother, who was sick with cancer. And I played a Mickey Mouse guitar that only had three strings on it and had to be retuned, and I sang terribly. I made up the songs, like “I love my grandma, and she loves me, I wonder if she can live forever!” She was my favorite. And my grandmother was a seer. There’s a difference between a psychic and a seer—psychics look at cards and try to tell you your future. Seers actually see your future. And my grandmother was real and very good at it, to the point where I remember her going to a person in the grocery store and saying “you need to go home right now, Harold needs you.” And I found out later that they got home just as Harold was having a heart attack, and was able to help him not have as much damage as there would have been if she hadn’t gone home. And my grandma would tell me…well, we were very poor. My mom was trying to raise seven kids in the sixties, when it was harder for a woman to get a job. My grandmother would tell me all the time that my stories would be my way out of poverty, and that I should always play songs and sing. So I would always tell stories. I would come home from school and she would say “what did you learn today?” And I’d say “well, we learned that Washington crossed the Delaware.” “And what would you do?” she’d say. And I’d say “oh no grandma, it was history, I wasn’t there.” She’d say “yes, but what did you do when Washington crossed the Delaware?” And she would keep pushing until I made up some fantastic story about what I did while Washington crossed the Delaware. So, I’d do that and sing because it made my grandmother happy. Then as I got older I started playing drums, and I got in a band with my older brother who played guitar—I didn’t learn to play guitar. And then we sorta started forming bands, and this was back in the Vietnam era when we all thought we were gonna be big rockstars. What ended up happening was, as I got older and started playing in clubs, I found out I was deathly allergic to cigarette smoke. I was singing and playing drums, which is very physical, and I had to have a bucket by the drums where I could go and throw up during breaks—it was just horrible. And I decided, well, this was the one time where my grandmother was wrong. And then, when I was going to Louisiana, the movie business basically died in L.A. So, movies went to Louisiana because of all the tax breaks. And then, on my way down there, I won the guitar in an arm-wrestling match.

EB: Now that’s a story.

Yeah, it was a story and a discovery. I never thought I was prejudiced, I thought I was a live-and-let-live guy, but I was headed across Texas in an FJ Cruiser, and looked down and the fuel light was on. I hit the GPS and it said the nearest gas station on the way was 100 miles. That wouldn’t do, so I reprogrammed it for one 15 miles off the next exit. I pulled into this little gas station/grocery store/garage/sports bar. They had two gas pumps, seven percent and diesel, like for tractors. And of course I go inside to use my credit card, and I go back through the little sports bar to the restroom. And for some reason they have this competition-type arm wrestling table set up. And this guy said “hey, you wanna arm wrestle for 20 bucks?” Well, I had calculated my gas and everything, and I was actually $80 short on the way to Louisiana. I had already got a place set up there, a studio apartment I’d put the deposit in for, and I was literally $80 short. I figured I’d put it on credit card. But I saw five guys, and twenty bucks each to beat them, so I started arm wrestling. I beat this guy, he said “double or nothing,” and I beat him again. Then they said “double or nothing, but now you gotta go against this guy!” I said, “okay.” The doubling had taken me up to $160. And then finally they said “okay, double or nothing for this guitar.” And by that time I had decided “oh, this is gonna go south.” I thought, even if I flatten these bastards out, because they’re rough-looking rednecks they’ll be trouble and want a fight. And I don’t wanna fight, because it’s a no-win situation. So, I decided I was gonna lose the next arm wrestle, that simple. Then this mechanic comes out the back, and he looks like Larry the Cable Guy on steroids. Holy shit! But, I don’t care, because I’m losing anyways. As he sat down, my stupid brain started wondering, “can I beat him?” And I had to find out. Well, I wound up beating him. And right after I beat him, I thought “oh shit, this is where the fight starts.” And so I just take the guitar and walk out the door, and I think “wow, these guys are actually gonna let me walk out.” So I just sat they’re thinking, we’re good. And then they come out, and I think this is where it’s gonna go down. At this point, I’m ready to use the guitar in the case as a weapon. And they say “don’t go down the way you came, go on this dirt road and it’ll take you right to the freeway, you won’t have to take the long route.” I sorta think “yeah, right.” But then I get in the car and use the GPS, and it takes me on the dirt road just like they said. And as I got on the freeway and started the rest of the way into Louisiana, I realized that I had just judged everyone of those guys in there for looking like me, basically. Thinking that they’re all assholes, and this is gonna turn into a fight. And as I thought about it, they were just a bunch of good ol’ boys who wanted to arm wrestle. The only asshole in the room was me, judging that they were assholes. So I got to Louisiana and opened up the case, and it was an Ovation guitar, like old Glen Campbell played. That’s what started me playing. And that guitar, after I had had surgery, fed me and paid my rent on the streets of New Orleans. …so the tour I’m on right now is just starting. And the most successful thing I have from this tour is a 102-year-old woman who managed to download my album, and contacted me and told me how much her husband George would have loved it. Every time she listens to it, it reminds her of George, and it’s just the highlight of her day. And she’s bugging me like crazy to put out the next one.

http://www.tomproctorandthealisters.com

Follow on twitter @tomproctorband