The film portrays an Arkansas fireman, fighting the demons of alcoholism and racism, who finds redemption in a faith he scorned.

The independent film “Paul’s Promise,” though set in 1950s racially divided Arkansas, addresses a very modern question: Can a racist fireman be redeemed and form healthy relationships with the people he once abused? Today a racist can lose his role and reputation in a single Twitter storm, but our society rarely leaves the door open for genuine recantation and redemption. This film explores these issues in a new way.

Written by Vitya Stevens, the film “Paul’s Promise” is loosely based on an out-of-print 1981 paperback “Brother Paul,” which its only two Amazon reviews have described as “powerful and inspiring” and “excellent.” Both the book and the film relate the real-life story of Paul Holderfield, a troubled white Southerner who moves from racism to reconciliation in a convincing yet surprising transformation. That the film also manages to find moments of wit and charm is a testament to director Matthew Reithmayr’s control of the material, which could have too easily stall and spin out in a field of cliches in the hands of a less accomplished filmmaker.

The setting is essential to the story. One of the most iconic photographs of the 1950s is the 101st Airborne, with steel helmets and automatic rifles, walking an 8-year-old girl to school in the face of the angry, jeering remarks of her classmates at the recently desegregated Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. Just across a concrete bridge from that grim scene, is the town of North Little Rock, where “Paul’s Promise” is set. Like it’s larger neighbor, North Little Rock is racially divided and resistant to reform efforts from the federal government and the larger culture. It is a completely unlikely place to begin a transformation away from racism. Holderfield, at the start of the film, is very much a man of his time and place – setting up the film’s intense drama.

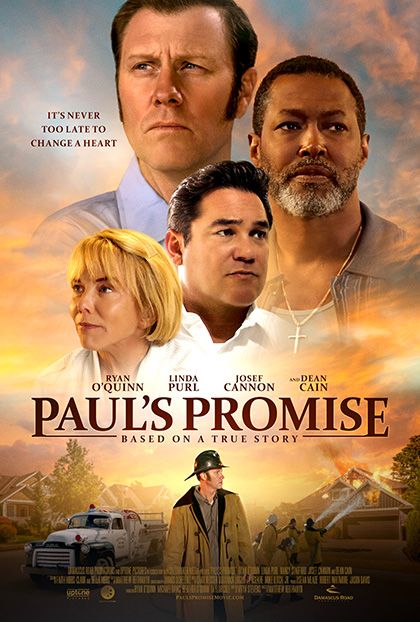

Paul Holderfield is a middle-aged fireman, who is addicted to drinking and angry outbursts and haunted by memories of his abusive and distant father. Played by actor Ryan O’Quinn, the character’s troubles are exacerbated when his aging mother, played by Linda Purl, is discovered to have aggressive tumors plaguing her kidneys and liver. This fatal diagnosis prompts a heightened concern for her son’s well-being as she prays for a change to take place within him. Holderfield’s wife, played by model Shari Rigby, radiates the frustration of raising two children in the face of her husband’s fury.

Holderfield is also burdened by the weight of a guilty conscience for sabotaging his childhood friendship with an African-American neighbor: He felt he had to choose between his friend and the acceptance of his racist peers. His choices as a child follow him into adulthood as he continues to appease his racially embittered co-workers. He appears to find little pleasure in this appeasement as his conscience nags him.

Holderfield’s former childhood companion, Jimmy Lipkin, masterfully played by Josef Cannon, is a devout Christian who has been praying that God would change the heart of his friend. In one of the most compelling moments of the film, Jimmy confronts his brother Tank, who is enraged after several black-owned homes were torched. Their dialogue provides a distinctly Christian perspective that is often lacking in popular conversations regarding racism. Tank is bitter and struggles to understand how his older brother remains calm in the face of adversity. Citing words from civil rights activist Malcolm X, Tank leans toward a militant approach in tackling racism. Jimmy encourages him to think differently by saying “I ain’t trying to be like Malcolm. I ain’t trying to be like Dr. King either. I’m trying to be more like Jesus. I believe that’s the only way things goin’ change if we follow Him.” These sentiments capture a perspective that is rarely portrayed in film, though it was often expressed by African-Americans at the time.

The power of a praying mother is a poignant theme in the film. Linda Purl’s character, Mama Holderfield, attempts to convince her son Paul to take her prayer list to church. He doesn’t treat her dying request with much seriousness. Purl’s character embodies persistence and hope as she trusts that God will save her son. In one of the significant scenes of the film, she expresses her optimism by saying, “God can change anything, even a man’s pride.”

Executive producers of the film include Mike Illitch Jr., Nick Logan, and Ty Nsekhe.

What makes this film distinct is that it presents Christianity as an answer to racism by providing a vehicle for personal change and growth. Whatever the viewer thinks of that perspective, it is debated inside a compelling story that shows real characters struggling with painful issues in complex, believable ways.

If you watch this film with family and friends, you will likely have a lively conversation on the ride home.

by Lennox Kalifungwa